North Africa in Exile: How Immigrants in France Engineered Decolonization

The untold political movements that emerged not in Algiers or Tunis, but in Parisian backstreets and factory floors.

Field Notes from the Edge:

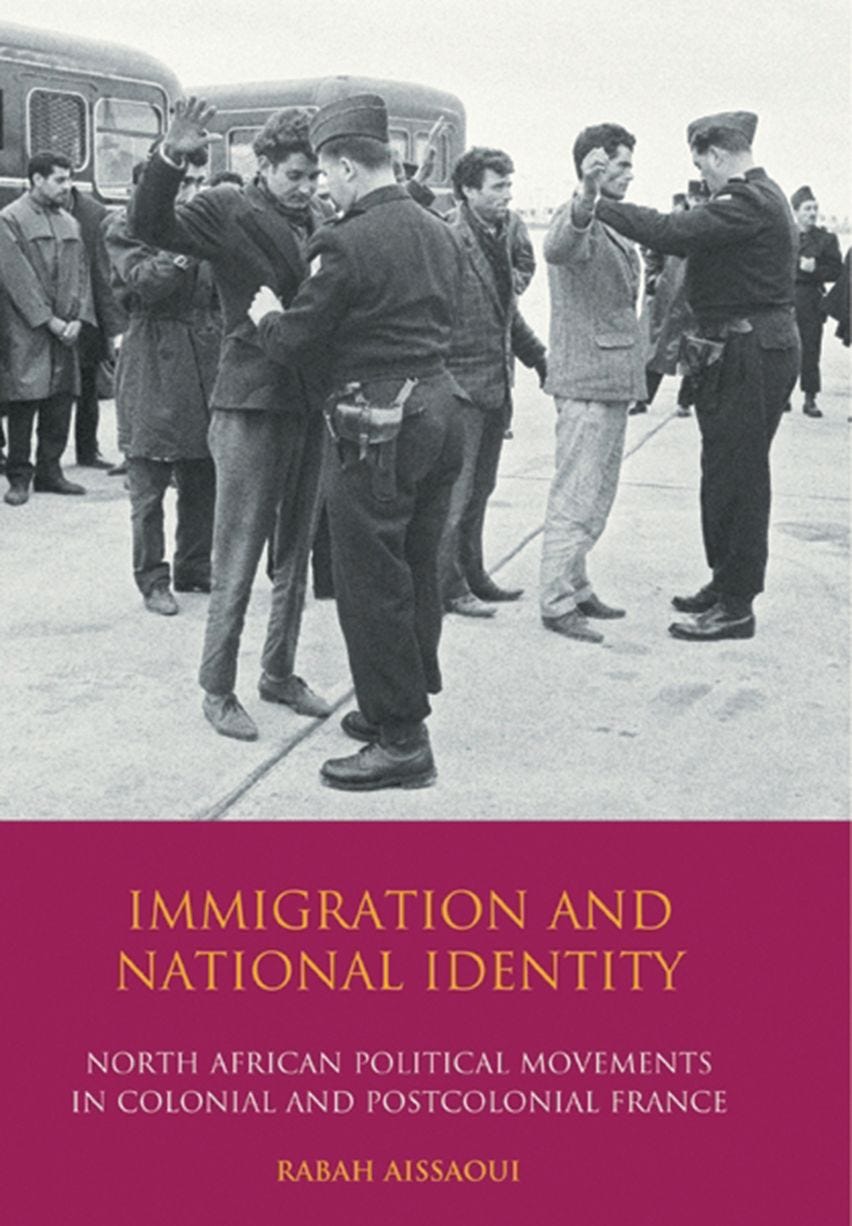

The dominant narrative of political change — especially in postcolonial contexts — often assumes that real transformation must happen on native soil. That revolutions are born in the capital, led by charismatic figures marching through the streets of Tunis, Algiers, or Rabat. But what Aissaoui’s work, Immigration and National Identity: North African Political Movements in Colonial and Postcolonial France (2009), reveals is that this idea is incomplete, even misleading.

The North African anti-colonial struggle wasn’t just a domestic affair — it was a transnational phenomenon, and France itself became a second front. Migrants, laborers, students, and exiles — often dismissed by both French authorities and nationalist elites as politically marginal — formed networks, published radical newspapers, met in cafés, organized strikes, and debated futures that their families back home could scarcely imagine under colonial surveillance.

In this light, the political agency of the diaspora subverts the notion that “real change” only happens “at home.” It suggests that “home” is not always a place on a map, but a community of shared purpose, and sometimes, being outside the nation gives you the clarity, safety, and distance needed to reimagine it.

The French state saw these migrants as cheap labor. The nationalist elites often saw them as too distant. But they saw themselves — rightly — as part of the struggle. Their exile was not a retreat; it was a strategic repositioning.

And so the lesson echoes today: meaningful political work doesn’t always happen in the center of power. Sometimes it happens in exile, in the margins — in the archives, in the fragments, in the in-between.

✒️ Story-craft & Strategy:

I chose to frame this week’s story around the figure of the North African migrant in France, not as a passive economic actor — as he was so often seen — but as a political agent operating from exile. This narrative choice is directly influenced by Rabah Aissaoui’s work, which challenges two stubborn assumptions:

That the only meaningful political resistance during the colonial period took place "at home."

That exile equals silence, submission, or assimilation.

What Aissaoui shows — and what I wanted to echo — is that France itself became an unexpected political terrain for Maghrebi resistance. These migrants, whether workers or students, were not disconnected from the independence struggle. They were central to it. Organizations like l'Étoile Nord-Africaine (ENA) or later the Front de Libération Nationale (FLN) used the metropole’s own civil spaces — unions, cafés, meeting halls — to build pressure on the colonial state from within its core.

From a craft perspective, this allowed me to contrast geographic displacement with political influence — to tell a story that moves against the intuitive direction of power (not from Paris to Algiers, but from Marseille to Constantine). I deliberately avoided framing these activists as exceptional individuals. Instead, I leaned on collective context: how a whole generation of immigrants in France constructed national identity not by dreaming of return, but by engineering rupture from afar.

In doing so, the narrative hopefully opens space for readers today — especially those in diaspora — to rethink where political agency begins. It’s not always in the capital. Sometimes it’s on the margin. Sometimes it’s in exile.

🌍 Fragments: Observations, Questions, Recommendations

🧠 Observation

In the early 1930s, the French police were more afraid of North African newspapers in Marseille than street protests in Algiers. Why? Because those papers traveled. They crossed borders, entered homes, and seeded ideas — silently, patiently.

The state feared not only what migrants did, but what they dreamed.

📚 Recommendation

To go deeper into the political agency of North African migrants in France, read North Africans in Contemporary France: Becoming Visible by Justin Gest. While more recent in focus, it examines the long shadow of colonial migration and how earlier political exclusion shaped generations of activism and identity negotiation in France.

You might also consult Todd Shepard’s The Invention of Decolonization, which critically explores how the Algerian War reshaped French republican identity — a perfect companion to Aissaoui’s exploration of identity-making from below.

❓ Question for You

Do you think people in exile today — economic or political — still carry the potential to reshape their countries of origin? Or has the nature of displacement changed in the digital age?

💬 Hit reply and tell me what “exile” means to you. Is it absence, freedom, or something in between?